Published February 02, 2026

How To Define A Task

Estimating time works best when progress is clear and bounded

Every task in trydeepwork asks a simple question: how long will this take?

Sometimes that question is easy to answer. Sometimes it feels strangely dishonest. That usually shows up when the work is not fully clear yet.

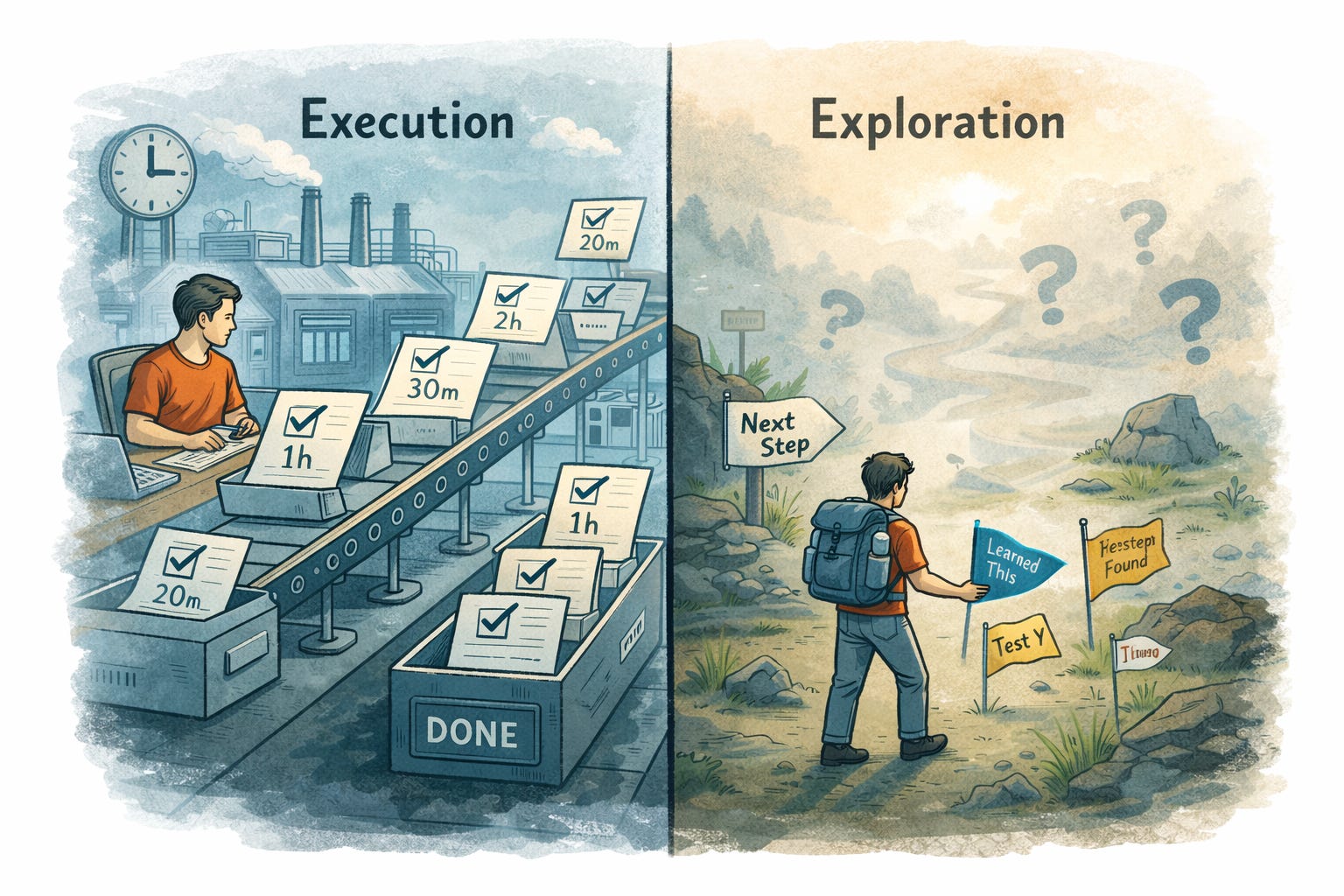

Task estimation assumes something very specific: that you already know what the work is, how to break it down, and what "done" looks like. That assumption holds for a lot of execution-heavy work like replying to emails, fixing a known bug, or refactoring a small, well-understood component. In these cases, estimation works because the shape of the work is already known.

But plenty of work does not start that way. Sometimes you are doing something for the first time. Sometimes you do not yet understand the problem space. Sometimes the whole point is to figure out what to do next. In those cases, estimating duration feels awkward because the question itself is premature.

What a task actually represents

We often treat a task as a container for effort, something like "work on X for N hours." But that framing is not very useful, because it tells you nothing about whether anything actually changed.

I have started thinking about it differently: a task is a unit of progress you want to notice and track. Not time spent or effort applied, but progress made.

When I cannot tell what changed after working on something, that is usually a sign the task was too vague to begin with.

What breaks with very long tasks

This becomes especially clear when a task stretches into tens or hundreds of hours. Over time, a few things quietly break:

- Completion becomes fuzzy. There is no clear sense of "done."

- Progress is hard to articulate. Each session blends into the next.

- Scope grows unnoticed. The task absorbs more and more work without anyone deciding it should.

We can keep logging time, but after a while we are no longer tracking progress. We are just tracking effort.

This is also where motivation starts to drop. I have felt this myself: logging time against the same task for a week straight starts to feel like feeding a spreadsheet, almost traumatic. It does not feel like progress. Working on the same never-ending task day after day is draining, even when things are moving. It is a feedback problem.

Why feedback loops matter

Small, bounded tasks create tight feedback loops: we work, something changes, we can tell what changed. That loop is what lets us reflect, learn, and adjust.

Very large tasks break that loop. Effort accumulates, but insight does not. Reflection stops being useful because it is no longer clear which effort led to which outcome. We are left with a vague sense that we have been busy, but not much else.

This is why I am opinionated about task size. The tool works best for tasks that can be completed within about a week, ideally somewhere between 30 minutes and 8 hours, with a clear sense of "done." It is about keeping the feedback loop intact.

When tasks are small enough, progress stays visible, completion feels meaningful, and reflection actually teaches you something. Beyond that size, tracking degrades quickly, at least in my experience.

But what about big, open-ended work?

Long-term projects are real. Exploratory work is real too. I have found that trying to represent all of that as a single task usually does not work very well.

Big work does not disappear, it just needs a different shape. Instead of one massive task, I try to ask: what can I do in the next few hours that would make progress feel tangible? That might look like:

- "Explore X and write down what I find."

- "Figure out the right next steps."

- "Test whether Y is worth pursuing."

I do not need full clarity upfront. I just need enough clarity for the next few hours. Exploratory work becomes a sequence of probes rather than a single blob of effort.

I am honestly not sure this works for every kind of creative or research work. That is why there is no hard limit on task duration. Some things genuinely resist decomposition. But it is a better starting point than a 50-hour task called "figure it out."